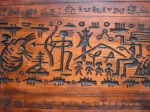

Six Arts of Ancient China

In ancient Chinese culture, to promote all-around development, students were required to master six practical disciplines called the Six Arts (liù yì in Chinese): rites, music, archery, chariot racing, calligraphy and mathematics.

In ancient Chinese culture, to promote all-around development, students were required to master six practical disciplines called the Six Arts (liù yì in Chinese): rites, music, archery, chariot racing, calligraphy and mathematics.

The study of rites and music instills in people a sense of dignity and harmony. The rites include those practiced at sacrificial ceremonies, funerals and military activities.

A famous saying of Confucius on music education is: “To educate somebody, you should start from poems, emphasize ceremonies and finish with music.” In other words, one cannot expect to become educated without learning music.

During the Shang Dynasty (circa 16th century – 11 century BC) and Zhou Dynasty (circa11th century – 256 BC), archery was a required skill for all aristocratic men. By practicing archery and related etiquettes, nobles not only gained the proficiency at war skills; more importantly, they also cultivated their minds and learned how to behave as nobles.

During the Shang Dynasty (circa 16th century – 11 century BC) and Zhou Dynasty (circa11th century – 256 BC), archery was a required skill for all aristocratic men. By practicing archery and related etiquettes, nobles not only gained the proficiency at war skills; more importantly, they also cultivated their minds and learned how to behave as nobles.

To become a charioteer is also an excellent form of training that requires the combined use of intellect and physical strength.

Writing, or calligraphy, tempers a student’s aggressiveness and arrogance, while arithmetic strengthens one’s mental agility.

Writing, or calligraphy, tempers a student’s aggressiveness and arrogance, while arithmetic strengthens one’s mental agility.

Men who excelled in these six arts were thought to have reached the state of perfection.

The Six Arts have their roots in Confucian philosophy. The requirement of students to master the Six Arts is the equivalent of the Western concept of the arts and skills of the Renaissance Man.

The elements of moral education, academic study, physical education and social training are present in the Six Arts – all attributes dating back to ancient times that are considered just as valuable in the modern world.

You must be logged in to post a comment.